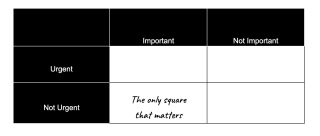

Many of us are familiar with the urgent-important matrix that divides tasks along these two dimensions. Its origins are with U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower and, later, famed self-improvement author Stephen Covey.

The common insight is that we should not mistake urgency for importance, and therefore avoid urgent but unimportant tasks.

This is a valuable insight. Indeed, research finds that we routinely prioritize responding to urgent emails over more important ones. It appears that despite being so widely known, the original message of urgent-important matrix still has something to teach us.

However, today I’d like to point out another insight from the matrix, one that’s less well-known but perhaps even more critical.

The only square that matters in the urgent-important matrix

Source: Generated by the writer.

Over the long-term, only one square matters in the matrix

Take a moment to look back over a long enough period of time: 6 months, a year, or more. Then, take account of your notable accomplishments during that time.

Next to each achievement note whether, at the time you were working on it, you considered the work important or not, and urgent or not.

If you are like most people, a clear picture will emerge: Most of our notable achievements over sufficiently long periods were ones that were important but not urgent.

Did you write a book in the past year? Chances are, you categorized it as something important, but never urgent enough to do just this minute.

Came up with a new strategy for tackle a vexing business problem? Likely, this required you to get away from the urgent everyday tasks of your work and devote time to something that may bear greater fruit at some point down the line.

Learn a new language? A new skill? Meet a major financial goal? The analysis would likely yield the same important-but-not-urgent combination.

All of these are examples of goals that are supremely important, but never urgent enough to drop everything to focus on right now.

Why? Important and non-urgent goals tend to be those that involve big ideas and big plans. These are the projects with an eye toward the future, toward expanding your business and bettering your organization and your life in transformative ways.

The new product that would upend an industry will likely emerge from months of important but non-urgent iterating on the current version. The new strategy that will lift your organization on the path toward success will likely emerge from important but non-urgent brainstorming with your team. The new book that will dislodge an antiquated paradigm will likely come from important but non-urgent deep thinking and writing.

But wait: Don’t urgent-and-important goals matter too? Yes, of course. However, paradoxically, those goals are easier to attain because we often let urgency dictate how we prioritize tasks. So, if we are fortunate enough to have a goal that is both urgent and important, it is virtually guaranteed that we will work on it in earnest.

We must ensure that non-urgent and important goal do not get left behind

There are several obstacles to prioritizing important and non-urgent goals. First, too often we submit to the tyranny of urgency and end up working on urgent and unimportant goals. Second, we procrastinate and are overly optimistic in assessing our ability to get things done when urgency is not there to push us.

So the question is: How do we avoid leaving important and non-urgent goals behind?

The first—but insufficient—step is simply awareness. Just knowing that our long-term successes will come from this part of the matrix is likely to put us ahead of the game compared to many.

More importantly, the key to giving important and non-urgent goals their due is being able to reduce urgency in our lives. The fewer urgent things we must deal with, the more we can prioritize based on long-term value. Certainly, removing urgent but unimportant goals should clear up our attention. But equally important, attempting to ensure that our important goals do not get to the stage where they are urgent is another worthwhile endeavor.

One way of reducing urgency is better personal organization and scheduling. This is an oft-repeated admonition: Be better organized and you will achieve more. There is truth to this: Think of prioritization as a skill, just like golf or tennis; the more you practice, the better you get.

Beyond this, another answer is delegation.

Delegation allows us to redistribute tasks that may demand immediate attention but are not core to long-term success. By assigning routine or less-critical responsibilities to others, we can free up mental and physical bandwidth. This should allow us to dedicate more time to cultivating long-term opportunities, developing skills, or addressing foundational issues that might otherwise be neglected in the urgency of day-to-day demands.

Delegation can be done by having another person handle all or most of our urgent tasks, but it can also be done in a fractional way, by identifying people who can target certain areas of our lives. These can be, for example, a financial adviser, a nanny, or a medical consultant, among other things. The idea is to pay a small short-term cost to invest in others who can share the burden of urgent tasks in order for leave space for long-term important and non-urgent goals that will give us a multitude of a return.

A final thought

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos is known for advocating the “regret minimization” framework for decision-making. In a nutshell, it dictates that decisions should be made based on whether they would produce the least amount of regret decades from now.

At the beginning of this post, we did a short look-back exercise and realized that many of the accomplishments we are most proud of were important but non-urgent goals at the time we got started on them. My guess is that the same will be true for our future accomplishments. To minimize regret and accomplish worthwhile things, do not neglect the important—and non-urgent—goals you have.