A framework to help design better “personal growth” apps.

The “personal growth” market—products and services which aim to help people develop in various aspects of their lives— is expected to experience significant growth over the next decade. This reflects an ongoing societal shift positioning personal development as a central source of meaning in people’s lives, particularly acute among Gen Z.

Catalysed by the pandemic, the digital delivery of “personal growth” through apps and online platforms has also spiked — from wellness (MyFitnessPal, Fitbod) to fitness (Strava, Runna, Nike Training Club, education (Duolingo, Headway) and mental wellbeing (Headspace).

While use of these apps grows, it is debatable whether or not they have a lasting impact on people’s lives. User retention rates for self improvement apps are low relative to apps from other industries, suggesting that they are struggling to help people overcome the challenge of keeping to a long-term development plan. Simply put, they are not helping people acquire knowledge and behaviours that “stick”.

To address this, apps are becoming more personalised. The rationale is that users withdraw from “personal growth” apps when their lived experience begins to feel disconnected from their digital experience; when content is misaligned with user goals, abilities and preferences. As a result, it is now common for these apps to surface specific learning resources on the basis of user context. Many allow users to track progress, or send messages of praise, feedback and support. Some, particularly in the Fitness space, record ongoing performance data and make minute, adaptive adjustments to development plans. These features reflect a model of personalisation in which content is matched by relevance to an increasing range of user data.

Yet they are still falling short. These approaches highlight the problem with traditional personalisation: they personalize by profile, through a reading of ‘who the user is’ rather than ‘what the user knows’. This renders the experience static, lacking the flexibility or precision to select information optimal to the needs of each individual while also failing to provide informal spaces for playful engagement, where learning truly takes place.

Lasting positive change will not occur in people’s lives unless apps move beyond personalisation through content matching and take into account how people actually learn and understand the world. To do this we can borrow ideas from the world of pedagogy—the methods and practices of teaching—and specifically its understanding of schemas.

Schemas are mental structures that organise knowledge in the mind through connections between related concepts. A child’s schema to understand ‘a river’ could be composed of connections between the concepts of ‘water’, ‘flow’, ‘nature’ and ‘boats’.

Popularised by Jean Piaget in the 1920s and 30s, schema theory built on this idea to provide a model of how learning happens— by people building connections in their own minds between new and familiar information. The child learning about rivers does so by bolting new concepts onto those they already have. The existing nodes act as reference points through which new knowledge is meaningful. New knowledge, like ‘people use rivers to travel’ would connect to existing concepts like ‘boats’ and ‘flow’.

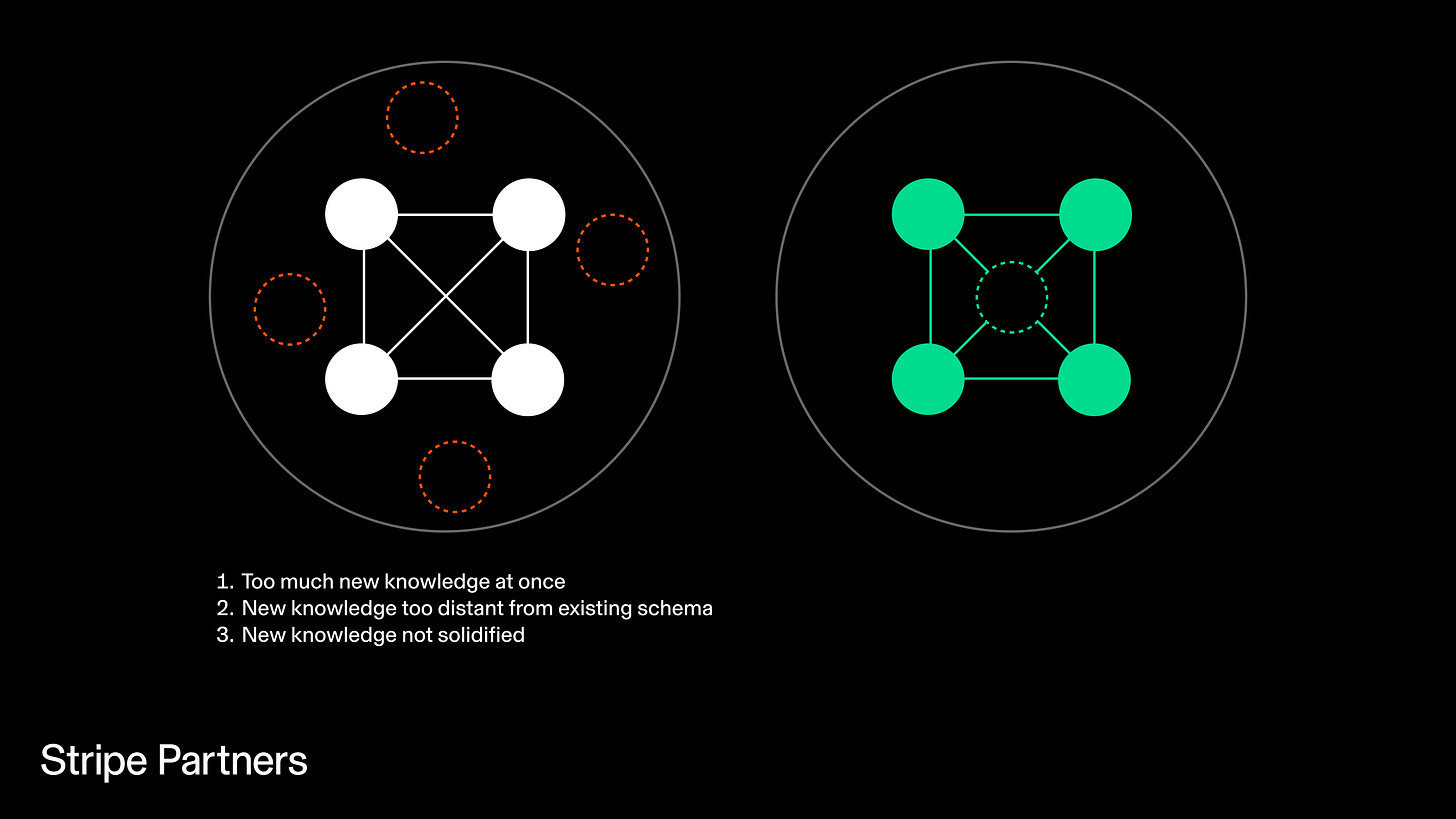

This model laid the groundwork for further developments in our understanding of the learning process. In the 80s, theorists came to recognise the effort, or ‘cognitive load’, required to form these new connections. They saw that cognitive load increases with both the quantity of new information introduced at once, and with its distance from existing schema. If these dimensions are not limited the student can experience ‘overload’, resulting in confusion and loss of learning. The child learning about rivers would be overwhelmed if flooded with large amounts of new learning at once, or if introduced to a single new idea that required a large conceptual leap from their existing schema, like ‘rivers are used to irrigate crops’. Conversely, beginning new learning by guiding the student from their understanding of ‘boats’ and ‘flow’ towards the idea that ‘rivers are used for transport’ helps this knowledge stick. The implications for teachers was clear; to allow new connections to form, new learning should be introduced in small chunks and be explicitly related to concepts students already know.

Schema theory also gave teachers a third key learning; that new connections need to be used, played with and applied to solidify. Each time a new connection is retrieved and used, the connection strengthened. It was in light of this insight that those within the social constructivist school of education theory emphasised the importance of low-stakes interpersonal communication to the learning process. They saw how quickly students learned new concepts, words and behaviours from their peers in the rough and tumble of social life. Teachers in turn recognised the need to recreate the dynamism and engagement of these social spaces in the classroom, where students could use, test, question, and ultimately embed new information within their schemas. Taken together these form the basis of foundational pedagogical principles for how teachers personalise learning to their students:

Introducing new knowledge in small chunks helps students to form connections without being overwhelmed

When planning a lesson, a teacher needs to make sure they’re not trying to cover too much too quickly, carefully sequencing new learning so students are given the time to form connections with each chunk before moving on.New knowledge sticks when it connects directly to existing schemas

Teachers explain new concepts using familiar language and examples, helping students connect fresh knowledge to what they already know. This makes learning more memorable as the links between existing and new understanding are explicit.

Students need time to practice, probe and play with new knowledge for new connections to solidify

Students can’t just ‘receive’ information, they need time to use it. Oral exercises such as discussions and debates, in which students freely express and engage with their new understandings, are integral to help new connections solidify.

Schema-based pedagogies can provide a blueprint for personalisation within “personal growth” apps. They begin from the principle that learning must be selected on the basis of what learners know, and that learning happens when they actively engage, question, play and interact with new knowledge.

Map the existing schema

Apps should prioritise using the range of user data at their disposal to meaningfully grasp what the user already knows, so proximal learning can be plotted. Apps could invite users to express their schemas using their authentic voice, mental models and train of thought, in order to build the foundations of future learning. In teaching, this exercise is referred to as ‘concept mapping’, and involves students expressing ‘everything they know’ about a subject prior to new information being introduced. This practice is well suited to AI voice conversation models which can understand and respond to the nuances of human speech with accuracy and truly engage with the idiosyncrasies of individual schemas.

Introduce select information in small chunks

Next generation “personal growth” apps could look to manage the cognitive load of users by ensuring new learning is introduced in small chunks which are proximal to an existing user schema. Rather than flooding users with expertise, they should look for these proximal learning opportunities, explaining new knowledge in terms the user is familiar with to make connections between new and existing knowledge explicit. For example, an AI could respond to a user’s specific existing understanding of a subject by providing clarification; ‘your understanding of ‘X’ as ‘Y’ is a good way of thinking about it, one point I would add is Z’.

Provide opportunities for low stakes exploration of new knowledge

Finally, “personal growth” apps could also use conversational AI to create informal learning spaces. Conversational AI features could enable “personal growth” apps to create informal, iterative dialogues between coach and trainee. These natural interactions provide a platform for users to practise and perform their new knowledge, crystallising connections in a low-stakes environment. A user could express their newly formed understanding on a subject as a stream of consciousness, and ask for specific feedback.

These techniques are social in their nature, but can be increasingly replicated digitally. Piaget believed that schemas develop most rapidly in social situations where low-stakes iterative cycles of teaching, learning and practice occur rapidly. It is in this process of query, expression and clarification that schemas clash and affect one another, where understanding builds, and knowledge shifts. By looking for opportunities to work with this interplay of schemas, “personal growth” apps can help new connections to form, and people to achieve the changes that these apps promise to deliver.

Interested in exploring similar topics further? Explore our archive of past Frames for fresh perspectives:

Many personal growth apps are centred around health—but how we understand health is changing rapidly in a post-Ozempic world. We explore this fascinating topic in detail here, as well as a general discussion of preventative medicine here.

In this piece—making tech for cyborgs—we redefine what a user even is, using ideas from Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto. This has implications on mapping a user schema. Where does the user end and the technology begin?

For another perspective on people and knowledge, check out this piece on embodied experiences and decision making. Here we apply ideas from Latour to help understand the role the body plays in how people distinguish between different “things” to make choices.

Frames is a monthly newsletter that sheds light on the most important issues concerning business and technology.

Stripe Partners helps technology-led businesses invent better futures. To discuss how we can help you, get in touch.